I remember that day so vividly, it’s hard to believe it’s been almost 60 years.

In the fall of 1963 I was in my senior year at NYU Heights. (See Ghostwriting in the Family and College Theatre)

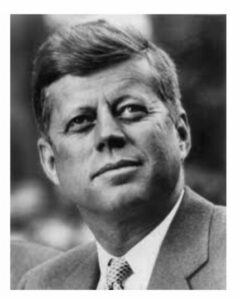

I was a member of the Hall of Fame Players, our college theatre group, and on Friday, November 22th we were rehearsing a play when someone came running towards the stage crying out that Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. Of course we stopped the rehearsal and amidst our shock, rage, and tears we disbursed. Some students rushed to their dorms to call family, some sought friends and sweethearts on campus, and others like me who were commuters headed home. Whatever classes any of us had later that day were either cancelled or we cut.

I regularly commuted by bus between the Heights’ west Bronx campus and my parents’ house in the east Bronx, and I clearly remember my bus trip home that day . Rather than full of the usual passenger chatter, the bus was eerily silent, as were the city streets we drove through – the same unsettling feeling that pervaded New York decades later on September 11th.

There were no cell phones then of course and apparently no one on the bus had a transistor radio that day – and we were all desperate to know what was happening in Dallas. Then, as a bus approached from the opposite direction, our driver slowed down and opened his window. The other bus driver did the same and leaned over to share the awful news that the bullet had been fatal.

When I got home my parent had the television on and, like the rest of the nation, we watched TV coverage of the assassination over the weekend and for many days to come.

On Monday I went back to campus where we assembled to hear the dean speak. Then the professor who taught my Chaucer course took the podium. That semester in class we’d been reading The Canterbury Tales in Middle English, but on that somber day our professor read the famous elegy by 19th century poet A E Houseman, To an Athlete Dying Young.

The time you won your town the race / We chaired you through the market – place; Man and boy stood cheering by / And home we brought you shoulder – high.

Today, the road all runners come / Shoulder-high we bring you home, And set you on your threshold down, / Townsmen of a stiller town.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away, / From fields where glory does not stay. And early though the laurel grows / It withers quicker than the rose.

Eyes that shady night has shut / Cannot see the record cut, And silence sounds no worse than cheers / After earth has stopped the ears.

Now you will not swell the rout / Of lads that wore their honours out, Runners whom renown outran / And the name dies before the man.

So before the echoes fade / The fleet foot on the sill of shade, And hold to the low lintel up / The still defended challenge – cup.

And round that early – laurelled head / Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead, And find unwithered on its curls / The garland briefer than a girl’s.

– Dana Susan Lehrman

– Dana Susan Lehrman

That poem has always brought me to tears and still does. It’s poignant and thought-provoking and makes one ponder the transitory nature of fame and glory. It certainly fit the moment … your professor clearly knew that. Very moving.

Thanx Ellen, but I’m sorry if I made you cry!

Hard to believe how many years ago that was.

Time is so fleeting. It hardly seems like all those years ago. I can still feel the silence & sadness.

Moving poem & your writing.

Thanx very much Joanie!

Lovely piece! I was not alive during the Kennedy era but was on campus on 9/11 and was even thinking, wow, that’s exactly how things were–classes were canceled and the whole town was somber all the way in Illinois. Funny how those moments stick in the memory. I’m glad you noted the connection.

Thanx Gigi, I guess the whole country was somber on those awful days.

Powerfully evocative piece Dana, especially the description of the bus ride home.

I didn’t know you were in a college theatre group, altho I do recall a framed photo in Belle Harbor of you standing beside a piano singing with a mic in hand!

Thanx Robin!

You were a kid when I was in college, but so sweet that you remember that photo in my folks house.

That was me as the torch singer Helen Morgan who traditionally sat on the piano – but on the college stage we only had that old upright!

We will never forget that day. Thank you for reminding us.

Thanx Paula, hard to forget.

How beautiful Dana, a poem is always timely.

Thanx Fred, my bookie friend!

That day and other tragic days seem to linger longer than happier ones. I wonder why. Because they are more life changing? Because their effects are more widespread? I always enjoy reading World Thru Brown Eyes.

Thanx Susan, I’m sure you’re right.

Here’s to happier days to remember.

I’ll always remember what I was doing when I heard and that weekend being in front of the tv.

Yep Midge, I’m sure we were all glued to the TV that day – almost 60 years ago unbelievably.

The seventeen most inspiring words in 20th century American history were spoken by John F. Kennedy mid-day January 20, 1961: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Though “the athlete dying young” was lost, his hope and idealism lived on in the work of so many, for sure in that of the young woman returning home on the bus.

Thanx Mike for your kind words.

I hope you and Joan are staying safe, miss you!